Maps of mushrooms

A few years ago, I wrote a small article for a friend’s zine about foraging mushrooms in tabletop roleplaying games. It proposed the player roll a dice and, depending on the result, they would get one of three outcomes: a list of ten edible mushrooms, a “null” result for inedible but inoffensive mushrooms, and a list of poisonous mushrooms of increasing lethality.

After finishing the piece, I thought the null result might be a bit disappointing and, as this was roleplaying games, the possibility of magical – as opposed to magic – mushrooms was obvious. I pitched a more wide ranging list, and this developed into a fictional guide to fantasy mushrooms, called Fungi of the Far Realms. As such I needed to do my research and have become quite a collector of mushroom books.

The majority are identification guides. It might seem that one would only need a single field guide to help you identify a plethora of mushrooms, but I’d like to explore this fascinatingly varied sub-sub-genre of book.

I grew up with bird-watching parents, and so the idea of a book just to identify things in the natural world wasn’t unfamiliar to me. Somewhere in my mum’s house there is a guide to birds of Europe with ticks in the corners of the ones my parents have seen, along with the names of countries where they were spotted in my dad’s looping copperplate. It is a deeply precious object.

I’ve never had the wherewithal to record my mushroom sightings with such precision though, and I don’t think I could. As a class of life, they are staggeringly diverse, with more discovered every year. Twenty three new fungi were formally described, the scientific equivalent of a christening, as opposed to four new birds. Moreover, to our eyes, they often look almost identical.

Generally speaking, fungi have two parts: first is the fruiting body. This can be a classic toadstool, a bloom of mould, a globular puffball, a nest of cups, a woody bracket, or seemingly innumerable other shapes. They have a similar purpose though, which is to project out and distribute spores. Most spores are microscopic, but if you see motes of dust streaming through a shaft of light cast by your bedroom curtains, some of the smaller dots may well be little baby mushrooms on their way to find a suitable place to settle.

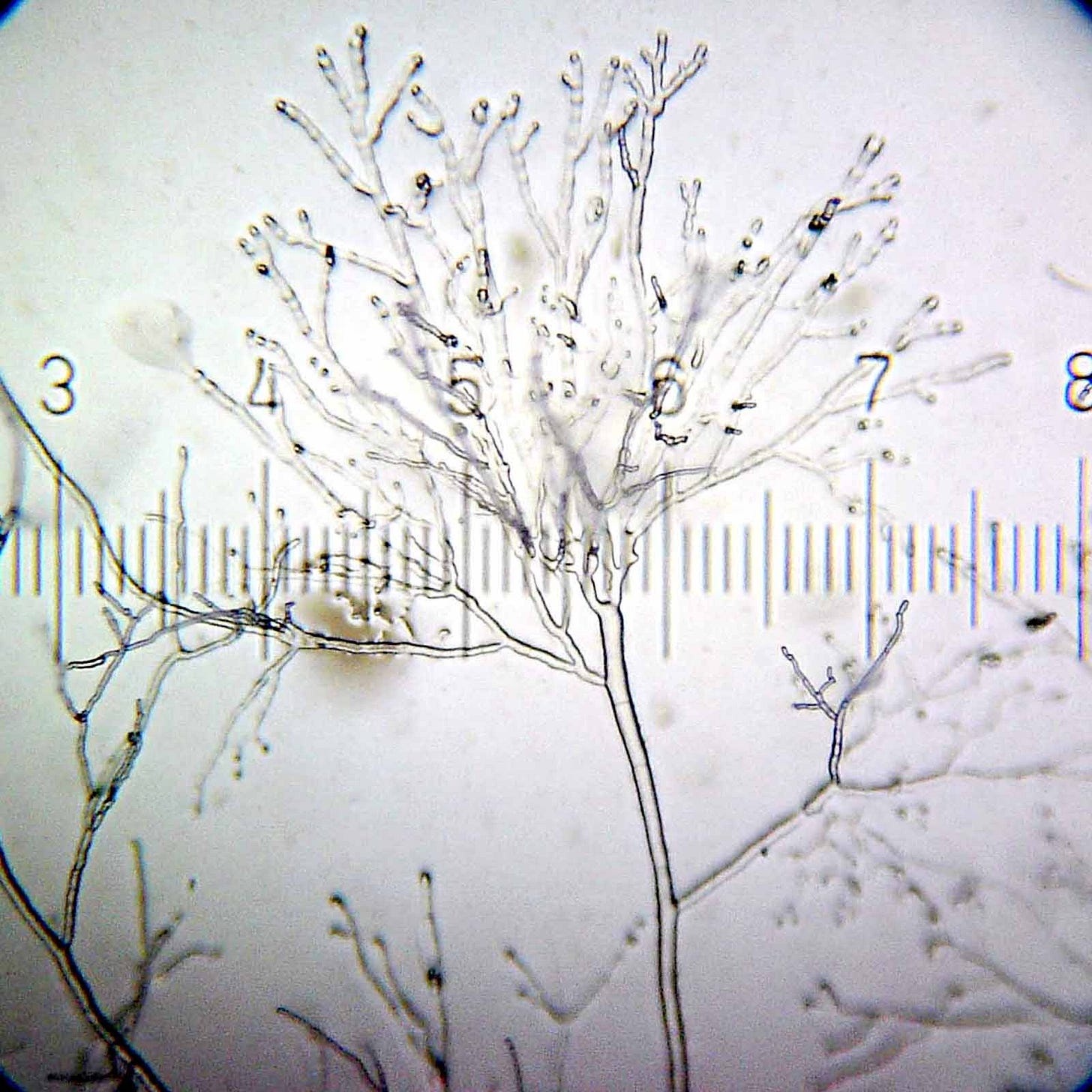

The second part of a fungus is the real body of the thing – the mycelium. This persists past a single season of growth and decay. It’s the part of the fungi that does most of the things we think about as constitute for living: it eats, excretes, respires and grows. And boy does it grow. Just when you see the first spots of green fur on the surface of jam, the entire jar will already be filled with a network of mycelium strands. You only see the fruit body of an established network, as fungi will wait until they’ve gotten all they can from a spot before expending energy on the visible growth. A mushroom sprouting signals that the mycelium is full, fat and ready to… propagate.

If you were to see a mycelium separate from the substrate of what it lives in, it would look like a network of fine white hairs. You usually can’t see it, however, not without specialist equipment, and certainly not on a walk in the forest. Seeing a mushroom is like seeing the egg of a bird, rather than the bird itself. So in some ways the only people with ticks in their mushroom identification guides should be mycologists and other professional peepers of microscopes.

That said, even the fruit bodies of mushrooms are sometimes so similar, that it’s only through extremely close observation that two species can be told apart. This is why new species can be discovered so readily – what seemed like one type, to scientists and experts, might be genetically very different.

Yet, there is a large demand for guides for another reason. Foragers are less concerned with the exact difference between mushrooms, and more with picking out the edible from the poisonous, rather like my original zine article. I should add that I’ve never met a forager who isn’t also just generally interested in mushrooms, and is as pleased to see a fly agaric as anyone.

Because of this, even the most sterile guides to mushroom often mark the poisonous from the edible, and even include tasting notes. That’s not just for the gourmands: mycologists will often nibble or lick a specimen to help identify it. They have a reputation among other scientists as somewhat eccentric, but it’s a well-established technique.

Personally, I’m not a fan of foraging, at least not in the UK. Our wild places are so thinned out by centuries of agricultural expansion, they can’t sustain much interference. I wish we had the same attitude to mushrooms as to wild flowers, that they are best admired in the context in which they grew, and left alone for another passersby to see as well.

Worst of all, locally foraged wild mushrooms have become a fashionable ingredient in high end restaurants. It’s not the head chef foraging for them, it’s teams of people going into the woods, picking everything they can see, and having an expert weed out the edible ones. Mushroom picking is banded in my local forest for just such a reason, but it’s difficult to enforce bylaws and it still gets swept clean from time to time.

Another kind of mushroom book I own are closer to art books. Large coffee table sized tomes with detailed explanations of the most unusual and beautiful, if not the most common, fungi from across the globe. One has detailed macro-photography, another beautiful illustrations. You would think that the art of traditional watercolour paintings were a facet of a bygone era of guides, but the opposite is true. Most of my more practical guides are illustrated, and the more aesthetic books are usually photos.

Partly I think this is just tradition. People want a guide that they expect, but it’s also just practical. Not only do mushrooms often look very similar, they are short lived, and change constantly. A newly sprouting mushroom of one type might seem superficially similar to the mature form of another. Rain and pests might rob a mushroom of a characteristic feature.

Photographers will search for a classic specimen, and work hard to get just the right shot to show off distinctive features, but they will rarely get a troop with different stages of growth all visible. Sometimes it’s better for a skilled artist to depict an idealised version of a thing so the viewer can understand that what is in front of them has certain aspects to look out for. The guide books are a map, but the mushroom is the territory.

The fictional guide I wrote is full of fungi that might exist within a fantasy world alongside elves and fairies. I wanted to make something that can be used in as many ways as a real guides. It’s got tasting notes for hobbits cooking up a hearty stew, and a list of hallucinations for when they aren’t as careful as they should be. I also wanted it to add something to games just by finding them. It’s written from the perspective of a fictional mycologist who offhandedly mentions stories, places and people that can add depth to games.

In my opinion, the best thing about it are the illustrations. Every entry, of which there are over 200, was hand painted by the phenomenal Shuyi Zhang. I didn’t know him when I started it, but it’s his book as much as it is mine, and I’m proud to have both our names on the cover. His playful style mimics the traditional, but imaginatively expands into something more fantastical. It’s utterly perfect for such an idiosyncratic book, and I’m constantly awed by the sheer amount of hard work and talent he displayed.